By Dan Proft

n 1981, President Ronald Reagan put a marker down for the rule of law when he fired more than 11,000 Federal Aviation Administration air traffic controllers who had walked off the job in violation of federal law, despite enjoying the backing of their union, PATCO, in the 1980 presidential campaign.

Is there a school board in Illinois willing to put a marker down for the next time its teachers walk the picket line?

In recent months, there have been three missed opportunities.

The 150 teachers at Prospect Heights School District 23 were out for a week in September before they came to terms with the board for a contract that provides a 14.25 percent pay increase over four years for teachers making less than $90,000 annually and a 9.75 percent pay increase over four years for teachers making more than $90,000.

Mari-Lynn Peters, the school board president, told me that for every job opening in District 23, the board receives 200 to 300 applications.

In October, it was the 248 teachers at McHenry County School District 156 who walked for a week. They agreed to come back after the board agreed to a 9 percent raise over three years in addition to splitting the cost of covering increased health insurance contributions.

Before the new contract, the average teacher salary in District 156 was just under $80,000, with 15 percent of teachers making more than $100,000 and two-thirds of teachers making more than $70,000. As in Prospect Heights, McHenry 156 board President Steve Bellmore told me that a substantial number of applications are received when there is a job opening in the district.

On Nov. 2, East St. Louis District 189 teachers returned to class after 21 days on strike with a four-year deal that provides an average salary increase of $12,834 over the life of the contract along with fully paid employee medical, dental, vision and life insurance (no deductible).

In East St. Louis, all of the more than 6,000 children in the district qualify for the free or reduced school lunch program. The median household income in East St. Louis is $19,000. The median pre-strike District 189 teacher salary was $72,000. Only 6 percent of East St. Louis students are deemed college-ready in spite of the fact that in the 2012-13 school year, East St. Louis spent $14,462 per student, compared with a statewide average of $11,483 among similarly sized school districts. And, when I say the district, I really mean the state of Illinois, because District 189 has been under state oversight since 2011 and receives two-thirds of its funding from state government.

My grammar school basketball coach used to tell us, “The graveyards are full of indispensable people.”

The school boards in Prospect Heights, McHenry and East St. Louis all had the opportunity to put that pithy aphorism to the test in an environment where it appears that demand for teaching jobs outstrips supply.

I understand why they demurred. Replacing people is no fun.

But no individual teacher or even district full of teachers is more important than moving the K-12 culture away from conferring salaries and benefits to the adults and toward schools that are child-centered and outcome-focused.

Some will dismiss this piece as an attack on teachers because it is easier to propagate the imaginary battle between pro-teacher and anti-teacher forces.

But someone has to put a marker down.

School districts throughout Illinois, including in the leafy suburbs, are following the trajectory of the bankrupt, junk-rated Chicago Public Schools.

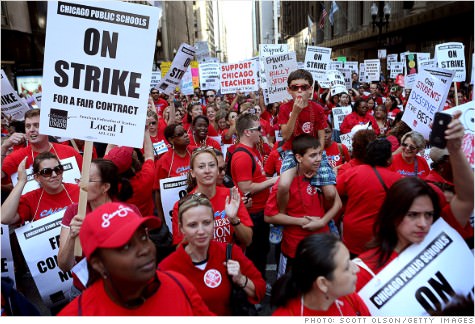

So it’s apropos that CPS is up next for its second teacher strike in five years.

Rather ironically, Chicago Teachers Union President Karen Lewis seems to be the last honest potentate in the Illinois edu-ocracy. To keep CPS teachers enjoying the lifestyle to which they have become accustomed, Lewis supports a LaSalle Street tax on financial transactions and a progressive state income tax, and she is open to a city income tax if that’s what it takes.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel and CPS chief Forrest Claypool pretend they can make a go of it at CPS with a $500 million state bailout of a system where a $1 billion annual budget deficit is the new normal.

Clearly the PATCO moment will not occur inside the leadership vacuum that is Chicago.

But it is going to happen if for no other reason than the axiomatic Herbert Stein’s Law: If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.

Our K-12 school systems cannot go on forever in their current form. Even if the will is weak, the math is inexorable.

This article was originally published in the Chicago Tribune on December 9, 2015.